Space

Space  Missions to Venus

Missions to Venus

Venus, the second planet from the Sun, has been visited by numerous missions since the space age began. It was especially targeted by Russian missions, as a better knowledge of the planet was eventually due to radar techniques. Venus before the space age, like Mercury, was a tough planet to observe. Although it's reaching higher altitudes above the horizon, Venus however is also remaining a mere morning or evening star. On the other hand, astronomers had soon discovered that Venus was permanently shrouded under a heavy cover of clouds. That was rendering vain any speculation about its surface, as it was preventing too any good assessment of how the planet's axis was tilted and of how, and in how much time, the planet was rotating about itself. Because Venus was roughly the same size as the Earth, scientists often called the two sister planets as little was known about the planet however. Some believed its climate was similar to Earthís tropics and young Carl Sagan only proposed that the known high concentration of carbon dioxide in Venusí atmosphere created a runaway greenhouse effect, leading to extremely high temperatures at the surface

The Mariners' Series

| Venus clouds as seen by Mariner 10 (visible, left; ultraviolet, right). picture courtesy NASA |

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, planned, developed and executed the first mission to Venus in about one year adapting the Ranger lunar probe that it was working on to build the 'Venus explorer.' The 447-pound spacecraft carried seven scientific instruments to study Venusí atmosphere and temperature, search for a possible magnetic field, and to study cosmic rays, the solar wind and cosmic dust during its trip to the planet. Planned as a two-spacecraft project, Mariner 1 launched first on July 22, 1962, but its Atlas-Agena rocket veered off-course and was destroyed in the first few minutes of flight, partly due to a missing hyphen in communications software. Mariner 2 followed on August 27 and this time the launch was successful. During the 110-day journey, Mariner 2 sent back valuable information about its interplanetary environment including confirming the existence of the solar wind. The spacecraft encountered several hardware anomalies but many of which inexplicably fixed themselves. By the time Mariner 2 approached Venus, one of its solar arrays had failed and the vehicle came dangerously close to overheating, but it remained healthy enough to complete its scientific mission. On December 14, 1962, Mariner 2 passed within 21,564 miles of Venus, and continued on in solar orbit, sending back the data it had collected. It measured the temperature at Venusí surface at 300°F to 400°F, confirming the greenhouse effect prediction, and the atmospheric pressure at 20 times greater than on Earth as such data were to be found even higher by following missions. The Mariner 2 had provided for the first some data about Venus, of which that its main characteristic was to be permanently veiled by a thick layer of clouds. Mariner 2 found that Venus has no appreciable magnetic field and therefore no protective trapped radiation belts, meaning the planet was constantly bombarded by cosmic rays. The spacecraft sent its last transmission on January 3, 1963, having completed the first robotic exploration ever of another planet. In terms of the JPL, Mariner 2 was the first of dozens of missions that explored all the planets from Mercury to Neptune. Mariner 5, in turn, grazed Venus by 2,500 miles (4,000 km) only in October 1967. Mariner 5 had launched aboard a Atlas-Agena rocket as it had been originally built as a backup for the successful Mariner 4 mission to Mars, and reconfigured into a Venusian mission, with a sunshield to keep the spacecraft cool and facing the solar arrays in the opposite direction. It had taken a 127-day flight from Earth, becoming the second successful Venus exploration mission in history. The spacecraft provided detailed information about the planetís atmospheric pressure and temperature as it found no radiation belts around and a weak magnetic field. Mariner 5 stopped transmitting on December 4, 1967. Venus was then visited in 1974 by Mariner 10 as the mission was heading to Mercury. Mariner 10 officially was a joint Venus-Mercury mission using a gravity assist at Venus, launched in 1973, as it passed within 3,580 miles (5,768 kilometers) of Venus on February 5, 1974. During the fly-by, Mariner 10 sent back information about the Venusí atmosphere and beaming back the first close-up images of the cloud-shrouded planet. Photographs taken in visible light revealed a featureless planet, but cloud detail was readily visible using ultraviolet filters. Mariner 10 returned 4,165 pictures of Venus. A unique opportunity was occurring in 1973 to send a spacecraft to visit both Venus and Mercury in a single mission. Using gravity assist, a technique theorized for decades but never used before, under favorable conditions a spacecraft sent to one planet can use that planetís gravitational force to essentially slingshot on to its next target. The method saved the cost of additional fuel and a larger rocket that would be necessary to launch the heavier spacecraft as well as time to get to the ultimate destination. In 1969, NASA approved a plan to send a spacecraft to Mercury, using Venus for a gravity assist. The mission, managed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, became Mariner 10. It was the last in the Mariner series. Mariner 10 carried out seven scientific experiments Ė the Television Photography System consisting of two telescopes to image the planet; an infrared radiometer to calculate the temperature of Venusí atmosphere; an ultraviolet spectrometer primarily to detect any atmosphere around Mercury; plasma detectors to study the solar wind inside the orbit of Venus for the first time; a charged particle telescope to study cosmic radiation; magnetometers to detect any magnetic field around Venus and Mercury; and a celestial mechanics and radio science experiment to investigate Venus and Mercuryís mass and gravitational characteristics. On Nov. 3, 1973, Mariner 10 lifted off from Cape Canaveral, Florida, to begin its journey to Venus and Mercury. Shortly after leaving Earth orbit, the spacecraft calibrated its camera system by taking photographs of the Earth and Moon. Planned course corrections 10 days after launch and on Jan. 21, 1974, adjusted the fly-by distance to within 8 miles of the target. The three-month cruise to Venus included several spacecraft malfunctions, overcome by the dedicated ground control team at JPL. In late January, Mariner 10 made ultraviolet measurements of Comet Kohoutek, adding to observations by ground-based facilities as well as the astronauts aboard the Skylab space station in Earth orbit. The spacecraft approached Venus from its night side, and passed within 3,584 miles of the planet on Feb. 5, 1974. During the fly-by, Mariner 10 performed flawlessly and sent back information about Venusí atmosphere and environment and beamed back the first close-up images of the cloud-shrouded planet. Photographs taken in visible light revealed a featureless orb, but using ultraviolet filters revealed extensive cloud details

The Soviets at Venus

In the 1960s and 1970s, as three American spacecraft made brief fly-bys of the planet and eight Soviet spacecraft attempted to land on it, with only the last four achieving that goal. One reason for the difficulty in the landing attempts was Venusí atmosphere. At the surface, temperatures reach 900° F and pressures are more than 90 times higher than at Earthís sea level. The success for the Soviets at Venus came in 1967, as it was eventually crowned by the only missions which ever landed at Venus. Between 1975 and 1981, the Veneras -- Venera in Russian stands for Venus -- 9 to 14 successfully landed on Venus' surface, each beaming back data and images during about one hour. A Venera-8 also had reached Venus by 1972 and was the first in the world to provide data about Venus (it was the twin to the Kosmos 482 the booster engines of which had failed to propell it off the Earth orbit as the probe kept since orbiting there). The two Soviet spacecraft, Venera 11 and 12, had launched in late September 1978 as they arrived at Venus a few weeks after the U.S. Pioneer Venus craft (check below). Each Venera consisted of a fly-by bus that released a softlander as it approached Venus. The Venera 12 arrived first on Dec. 21 and Venera 11 four days later. Two days before their encounters, the main spacecraft released their landers that made independent descents through the atmosphere while the buses flew by Venus and continued on into solar orbit. Venera 12 transmitted data from the surface for 110 minutes and Venera 11 for 95 minutes. Unfortunately, the lens covers on both spacecraft's cameras failed to jettison and no color photographs of the surface could be obtained. The soil chemistry analyzer on both landers also failed to operate. The landers however did return much useful information about conditions at the planet's surface from their landing sites 500 miles apart. The USSR launched also two spacecraft carrying Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) instruments with large antennas, and Venera 15 and 16 entered polar orbits around Venus in October 1983 mapping the surface to a resolution of 1 to 2 kilometers. Two futher Soviet missions -the Vega 1 and Vega 2- released probes and landers at the planet in 1985 as they were en route to the comet Halley. The last Veneras performed radar studies too. The Soviet landers allowed to discover a weird surface, with large basalt slabs, rocks, and fine-grained soils. Such landscapes were assimilated to some Earth's volcanic equivalents. None of the nine Soviet probes which achieved landing at Venus, lasted longer than 127 minutes

| Venus surface as seen by USSR's Venera 13. picture courtesy NASA/NSSDC |

The Pioneer 1 and 2

The US Pioneer 1 and 2, in 1978, were the first missions which used radar instruments at Venus to pierce the clouds to study the surface. One of the missions orbited Venus as the other released four probes into the atmosphere. Three of the probes were targeted at different parts of the planet. The Pioneer Venus project, which was managed by NASAís Ames Research Center in Californiaís Silicon Valley, was a project which consisted into two spacecraft built. The first spacecraft, Pioneer Venus Orbiter, was to launch first and remotely gathered information to analyze Venusí atmosphere using a suite of instruments. The second spacecraft, Pioneer Venus Multiprobe, contained several entry probes to collect data on the atmosphere from the cloud tops all the way down to the surface at several sites around the planet. It featured the main spacecraft, the large probe and three identical small probes named North, Day and Night. A NASA Science Steering Committee in 1972 listed 24 important scientific questions at the forefront of Venus research, and the Pioneer Venus project addressed 23 of them. A total of 114 scientists were associated with the Pioneer Venus project, representing 34 colleges and universities, 14 federal laboratories and 15 industrial laboratories, as well as 10 foreign countries. Despite its proximity, relatively little kept being known about the planet in the late 1970s, especially its lower atmosphere. The thick atmosphere, composed of more than 96% carbon dioxide with clouds of sulfuric acid, prevented direct visualization of the planetís surface. Pioneer Venus Orbiter launched first on May 20, 1978, from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station atop an Atlas-Centaur rocket. The Pioneer Venus Orbiter is also known as Pioneer 12 or Pioneer Venus 1 (the Soviet Union also took advantage of the launch opportunity at that time to dispatch two spacecraft to explore Venus, the Venera 11 and 12, launching Sep. 9 and 14 respectively. By the fall of 1978, when all components counted, a fleet of 10 spacecraft were on their way to Venus). Mission planners chose a longer 7-month trajectory to Venus that ensured a slower speed when the spacecraft arrived at its destination, thereby saving fuel required for the orbit insertion burn. Insertion into Venusí atmosphere occurred December 4, 1978. Pioneer Venus Orbiter carried 17 scientific instruments to study the planetís atmosphere during its planned operational life of one Venusian day, equivalent to 243 Earth days. Pioneer Venus Multiprobe launched in August, launched on an Atlas-Centaur rocket from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida, but on a faster trajectory ensuring both spacecraft arrived at their cloud-shrouded destination within a few days of each other in December. The two Pioneer Venus spacecraft gathered and transmitted to Earth a wealth of new information about Venus. The Pioneer Venus Orbiter measured data from the upper atmosphere and southern region of the planet, including interactions between solar winds and Venusí magnetic field. The ultraviolet light photographs it took showed dark markings in Venus's cloud tops, and it detected radio signals from the planet revealing almost continuous lightning activity in the atmosphere. It also mapped Venusí surface at 93 percent through its radar experiment. The spacecraft confirmed an atmosphere with clouds, mainly of sulfuric acid, with little magnetic field. Additional topography studies found the planet to be generally smoother than the surface of Earth, but Venus has a mountain higher than Mount Everestís peaks and a chasm deeper than the Grand Canyon. Carrying seven experiments and fitted with a parachute to slow its descent into the atmosphere of Venus, the large probe studied the composition of Venusí atmosphere and clouds as it also measured the distribution of infrared and solar radiation. The three small probes were designed without parachutes, each carrying six experiments. Each probe targeted different parts of Venus. North entered Venus at the high northern latitudes, Night targeted the night side at mid-southern latitudes, and Day targeted the day side at mid-southern latitudes. All probes were carried by the Multiprobe spacecraft Bus. Amazingly, two of the probes survived touchdown and continued to return data from the surface - Night Probe for just 2 seconds (it likely tipped over after landing) and Day Probe for 68 minutes. Finally, the Multiprobe spacecraft Bus burned up as expected at an altitude of 75 miles, providing data for 2 minutes on the planet's upper atmosphere. The main spacecraft carried an additional two experiments designed to study Venusí upper atmosphere. The five probes collected detailed information about atmospheric composition, circulation and energy balance. The large probe separated from the main spacecraft 123 days after launch, on November 16, followed by the small probes on November 20, reaching and entering Venusí atmosphere December 9. While the Multiprobeís mission was brief once it arrived at Venus, the Orbiter far outlasted its expected lifetime, transmitting data about the planet until 1992, by which time the Magellan radar mapping spacecraft joined it in orbit to continue detailed Venus observations. During its years of operation, scientists used the Pioneer Venus Orbiter's ultraviolet spectrometer to study seven comets, including Comet Halley in 1986. With its fuel reserves exhausted, after spending 14 years conducting research along 5,055 orbits, Pioneer Venus Orbiter plunged through Venusí atmosphere, burning up as it did so on October 8, 1992. check a map of Venus compiled from data recorded by Pioneer Venus Orbiter spacecraft (courtesy NASA/Ames/U.S. Geological Survey/Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

| Maat Mons, a 5-mile (8-km) high volcano. picture courtesy JPL |

The Magellan Mission

| Three impact craters in Lavinia Planitia. picture courtesy NASA |

The last and most comprehensive mission to Venus dates back to 1990 when the US, Magellan mission reached there and spent 4 years in orbit, mapping the surface in the radar range. The mission had first been called the Venus Radar Mapper as Magellan became the first planetary probe to be launched by the Space Shuttle. 98 percent of Venus were mapped this way. Radar missions, and Magellan, further confirmed that Venus has been mainly shaped by volcanism. At least 85 percent of the planet's surface is covered with volcanic flows which formed plains, with small and large volcanos, as a complete lack of water avoided any form of erosion. Surface features, thus, were able to persist during hundred of millions of years. The atmosphere of Venus is surely a more important erosion agent with its high temperature of 900°.F (475°C), a strong atmospheric pressure of 92 bars, and sulfuric acid rains! Clouds have been measured to be 18.5 to 24.8-mile (30 to 40-km) thick, with their bases lying at 18.5-21.7 miles (30-35 km) above the surface. It's still unknown whether Venus' surface was shaped by a single event some 500 million years ago or whether the planet endured several successive lava flows and volcanic processes. Some imposant moutain ranges exist too, as the surface has been impacted by numerous craters. No plate tectonics exists. Venus possesses a so-called atmospheric magnetosphere. Although the planet is rotating two slowly to yield a magnetic field, the solar wind is however somehow halted by the interaction between the planet's upper atmosphere and ionosphere, and the solar wind. On Oct. 13, 1994, after a series of controlled engine firings lowered its orbit, Magellan entered Venus' atmosphere and burned up, after more than 15,000 orbits

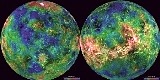

| click to a view of how the Magellan data, which had mapped more than 98 percent, were addded by 2010 with images from the Arecibo radar in a region centered roughly on 0 degree latitude and longitude, and with a neutral tone elsewhere, primarily near the south pole. That composite is color-coded for elevation (gaps in the elevation data were filled with altimetry from the Soviet Veneras and the Pioneer Venus mission). picture courtesy NASA/JPL/USGS |

Website Manager: G. Guichard, site 'Amateur Astronomy,' http://stars5.6te.net. Page Editor: G. Guichard. last edited: 5/20/2019. contact us at ggwebsites@outlook.com